“. . . I think trees represent something I inherited from far, far in the past. There is something psychological here, for I obviously feel that a landscape with trees is preferable to scenes without them . . . There is also a big difference between realizing and not realizing that the trees alive today have been living on this earth far longer than we humans can even imagine.”

(Hayao Miyazaki, Starting Point: 1979–1996, p. 163)

I’ve Been Lost in the Woods

My 2023 summer screening experience of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) was perhaps one of the most probing watches of a Studio Ghibli film ever. This was not my first go-round with Nausicaä (my family has owned a DVD copy of it since my childhood), but I’m willing to call it the viewing where I actually understood more of what was happening than not.

Nausicaä is neither a convoluted film nor a particularly difficult one to understand. Anyone who watches it generally takes note of themes like compassion for the other, exploitation of natural resources, and struggles for ecological balance to name a few. And many, many viewers become sucked in by the gravity of Nausicaä’s glowing forestscape, which is exactly where I’ve been wandering since that 2023 theatrical showing. At some point, I felt compelled to order a dinged up yet discounted copy of the Nausicaä manga courtesy of VIZ and RightStuf (R.I.P.), yet I shelved it upon arrival for future me to explore.

Flash forward to the following summer and I find myself this time at a showing of Princess Mononoke (1997). Now, GKIDS has been graciously offering “Ghibli Fest” screenings for several years. What brought me to see this Miyazaki masterpiece specifically one year after the previous? I’m blaming it on the trees, for when I walked out of the theater and warmly beheld the setting summer sun, I felt a burning resolve to learn more about forests in Japan. As soon as I returned home, I ordered books, cleared off my table, and let the stacks grow until they toppled over.

It’s now January 2025, and after procrastinating on writing something blog-worthy to encapsulate “where” I’ve been the past year and a half, I’ve decided that I’m ready to turn the leaf and confront the forest head-on. Here is how I learned more about the history and geography of Japanese forests through Hayao Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli.

Why a “Guide” Instead of an Analysis?

In an age where we have access to anything we could ever want to know, right at our fingertips, we have become consumers who seek only the answers to surface-level questions and some of life’s greatest dilemmas alike, and we have neglected the vital process of learning through experience and reading. By my handpicking these films, essays, and excerpts and organizing them in a methodical and practical way for you yourself to learn what these works are doing and how they are doing it, you will walk away with an immensely richer and profoundly deeper understanding of forests in Ghibli works—that, I promise you. Hard work offers fulfillment. Miyazaki himself says it best: “To want to work is to want to live” (Turning Point: 1997–2008, p. 240). If you truly want to get in the weeds of this topic like I did, then it’s time to roll up your sleeves.

The subject of this post is not what I learned, but how I learned. There are countless reviews, both formal analyses and informal reflections, written posts and published videos, that cover what we can learn from Ghibli works. I might contribute to that discussion, but that’s for a different post. My intent here is to show you how I stumbled into this topic, hence this diary of an opener. I want to document how I became lost in the forest’s vastness and offer you a guide to staying above the treetops (or more of a thread to trace) should you find yourself also wanting an invitation to this little party in the woods. (No weird stuff, unless you count the clattering kodama.) Just know, though, that life starts on the forest floor—down in the weeds, the burrows, and the soil itself. It’s a little more fun there, anyhow.

If you know of other supplemental materials to this broad topic of “Ghibli forests,” leave a comment below. If it’s knowledge you’re willing to share, I welcome your recommendations.

So, Where to Start?

I’m no forest ranger (nor much of an outdoors person, really), but I do know that most if not all forests have multiple entrances. Naturally, so do we, too, have many options for embarking on our journey. Of course, whenever “starting” is concerned, I will never fault one for defaulting to theatrical release order. Much insight can be gained by tracking how a writer or director progresses through their career. However, given the universality of Ghibli these days, chances are high that you’ve seen one of their films already; you already have memories and visitations with one or more of these titles, and a truly “ blind chronological viewing” may seem less attainable.

To me, it’s more fruitful to consider the scope of each major Studio Ghibli film that centers “the forest” as its setting. Three major films come to mind: Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), My Neighbor Totoro (1988), and Princess Mononoke (1997). While most materials I fold under each major film are directly related to said film, some works are ancillary. So, I want you to consider this method of organization as well:

- To humanity, from the past

- To humanity, from the future

- To humanity, living in the present

As I’ve read more essays and speeches by Miyazaki, I’ve come to see him as a man of many contradictions. Publicly, we perceive him as a genius who gripes endlessly about how miserable life in present-day society is—whether in the 80s, 2000s, or now—which consistently leads to further disgruntlement with matters concerning our bleakening future. At the same time, he remains optimistic about children, their innocence, and their ability to make positive impacts. (I wonder how much this has changed since his interviews in the early 2000s . . .) In private, Miyazaki has devoted much time to unraveling the mysteries of Japan’s ancient past. And, while a childlike fascination pokes through his musings on what life must’ve been like during the Jōmon, Heian, or Muromachi periods, he openly confesses that life “back then” also had its abundant misfortunes. Wherever there are people, there are problems, it seems.

What I’m trying to get at is that Miyazaki’s intentions with communicating timely issues are also informed by the genre types his works resemble: historical fantasy (period drama, specifically jidaigeki style), post-apocalyptic fantasy, and rural fantasy. This is where I derive the aforementioned past-future-present structure from.

Thus, let me then offer you the roots, bark, and branches for this method of attack, starting with what can only be described as one of anime’s most compelling and cinematic experiences to date. That’s right. We first head off to industrial Irontown where the fierce Lady Eboshi wages a one-sided war with the creatures of the forest—and the forest itself.

Forest of Historical Fantasy

“There is a religious feeling that remains to this day in many Japanese. It is a belief that there is a very pure place deep within our country where people are not to enter. In that place clear water flows and nourishes the deep forests . . . The forest that is the setting for Princess Mononoke is not drawn from an actual forest. Rather, it is a depiction of the forest that has existed within the hearts of Japanese from ancient times.”

(Hayao Miyazaki, Turning Point: 1997–2008, p. 88)

WATCH: Princess Mononoke (1997)

I fancy beginning with a watch of Princess Mononoke because it packs a whole lot into its 133 minutes while feeling complete on its own. You are introduced to conflicts that form the epicenter of the whole reason why we feel this disconnect with nature to begin with: nature vs. industry, humanity vs. spirit, tradition vs. change. With its sweeping visuals and epic scale, the film invites the viewer to explore what it means not only for one person “to live” but for tribes of people, races of creatures, and forces of nature to all “live” within the same world, even if they exist so in cyclical conflict.

SUPPLEMENT: The Art of Princess Mononoke (VIZ Media)*

After enjoying such an incredible film, re-experience the magic of the forest with its art book! Notice the contrast in surroundings between Emishi Village and the Tatara Ironworking Clan. Most of those lush forest backgrounds can be found in the “Forest of the Deer God” section (pp. 83-115). VIZ has released English editions of these art books for each Ghibli film by Miyazaki, so check out the art books for the other films mentioned in this guide too.

*At some point before or after the film, be sure to read the director’s statement “The Battle Between Humans and Ferocious Gods” dated April 19, 1995. You can find it online or printed in various locations: The Art of Princess Mononoke (p. 12), Starting Point: 1979–1996 (p. 272; slight differences due to being a planning memo), Turning Point: 1997–2008 (p. 15), and the GKIDS Blu-ray release insert (p. 5). I always enjoy reading statements like these prior to watching a film, but I can respect wanting a 100% blind experience for first-time viewers.

READ: Starting Point: 1979–1996 (VIZ Media)

The two essay and interview collections by Hayao Miyazaki are DENSE but fascinating to read, whether by section as needed or straight through like I did. I recommend the entire publication, but relevant passages and starting pages are as follows:

- Princess Mononoke Planning Memo (p. 272)

- About Period Dramas (p. 132)

- The Power of the Single Shot (p. 158)

READ: Turning Point: 1997–2008 (VIZ Media)

Unlike Starting Point, which describes many of the early ventures leading up to some of Miyazaki’s biggest works of the 2000s era, Turning Point goes all-in on five distinct and classic titles. Princess Mononoke starts the ball of this 450-page book rolling with nearly 200 pages dedicated to it and other social happenings as the film was being made. Really, it’s all insightful knowledge, but the following excerpts especially set a solid groundwork for the next leg of our forest journey.

- The Battle Between Humans and Ferocious Gods—The Goal of This Film (p. 15)

- The People Who Were Lost (p. 20; poem)

- Kodama Tree Spirits (p. 24; poem)

- The Forest of the Deer God (Forest Spirit) (p. 26; poem)

- The Elemental Power of the Forest Also Lives Within the Hearts of Human Beings (p. 27)

- Those Who Live in the Natural World All Have the Same Values (p. 38)

- You Cannot Depict the Wild Without Showing Its Brutality and Cruelty: A Dialogue with Tadao Satō (p. 42; comments on the tagline “Live” on p. 54)

- Princess Mononoke and the Attraction of Medieval Times: A Dialogue with Yoshihiko Amino (p. 60)

- Forty-four Questions on Princess Mononoke for Director Hayao Miyazaki from International Journalists at the Berlin International Film Festival (p. 79; comments on how “The kodama came from the eeriness and mysteriousness of the forest” on p. 82; comments on the “depiction of the forest that has existed within the hearts of Japanese from ancient times” on p. 88; comments alluding to biocentrism vs. anthropocentrism debate on p. 90)

- Animation and Animism: Thoughts on the Living “Forest” (p. 94)

- We Should Each Start Doing What We Can (p. 276)

WATCH: The Man Who Planted Trees (1987)

This 30-minute animated short film directed by Frédéric Back (based on Jean Giono’s 1953 short story) is a source of personal inspiration for countless animators, Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata included. At its core is the simple ethos of “paying kindness forward by hard, consistent work,” yet the film’s animation of plants is constantly vibrant and full of motion. Back was a master of the craft, no doubt, and while viewing it online in 480p is far from ideal, you can watch his work HERE on YouTube for free.

After watching this, return to Starting Point: 1979–1996 and read “Having Seen The Man Who Planted Trees” (p. 143) for brief comments by Miyazaki himself. Ghibli director Isao Takahata’s love for the film is mentioned in other documentaries as well, namely Journey of the Heart: Conversations With The Man Who Planted Trees. Traveler: Isao Takahata (1998).

And now, to get to the heart of these matters concerning the forest, we actually head out to a valley. A valley of the wind.

Forest of Post-Apocalyptic Fantasy

“I’m sometimes asked what it is about trees that I find so attractive. But it seems to me that even the question represents the height of irreverence. After all, our lives depend on trees, and we exist at their mercy. For example, I believe that we will one day pay a terrible price if people arrogantly and indiscriminately destroy forests, simply because they want ‘a more profitable use of the land.’ In fact, we’re already paying the price.”

(Hayao Miyazaki, Turning Point: 1997–2008, p. 276)

WATCH: Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984)*

For people unacquainted with Nausicaä in any form, I will almost always fight for a film watch prior to reading the manga. Hear me out. The film is a good one. It has spellbound literally generations of aspiring artists, animators, and anime fans, and you will never regret being able to say “The manga was better” over “The movie was terrible.” Because it’s not, and now you know.

Personal opinions aside, a watch of the film before a read of the manga might also be wise since the manga didn’t conclude until 1994 with over 12 years in the making. Miyazaki’s editor paused the manga’s serialization several times to allow the writer/director/artist to clear his head by working on films. (Or maybe it was the other way around; Starting Point provides the full picture.) Although the final theatrical product reflects characters, ideas, and setting details from only the first part of the manga, it remains historical in its effect of inspiring all who witness the flurry of forest life bursting forth from the Sea of Corruption.

*Don’t forget to read the statements from Toshio Suzuki (2010), Hayao Miyazaki (1983), and Isao Takahata (1983) before OR after watching the film. The only format I presently own these in is the GKIDS Blu-ray release insert, though I’m sure they can be found online or in print elsewhere.

READ: Starting Point: 1979–1996 (VIZ Media)

We’re back to reinforce our film watching with essays, interviews, and other tangents from the director himself. Because this is the only Miyazaki film with a manga adaptation penned by the director, the dual perspective is fascinating to read up on from a creation standpoint. Read any of this before, while, or after reading the manga. Then, focus on the forests, which I’ve done for you by selecting these particular passages:

- On the Banks of the Sea of Decay (p. 165)

- About Ryōtarō Shiba-san (p. 211)

- On Nausicaä (p. 283)

- On Completing Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (p. 390; about the manga)

- Earth’s Environment as Metaphor (p. 414)

READ: Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (VIZ Media)

Of course, if you start with the film, you’re more likely to appreciate what the animated story has going for it. If you’re in the manga-first camp (a rare breed), then you probably don’t bat an eye at the film, and that’s ok. The Nausicaä manga is one of the most significant achievements in comics, but I probably didn’t need to tell you that. As someone who only finished reading it for the first time at the end of 2024, I was stunned by the piece. Through the Daikosho, we see how reclamation of forest land can be both a natural process and one that’s artificially engineered. And with the theatrical tagline of Princess Mononoke sharing the same word as the final line of the Nausicaä manga—that we must “live”—I surrender to the hope that no matter how much of the forest we take, the forest will find a way to live on—to outgrow us, even.

Forests of Rural and Urban Fantasy

“We Japanese have changed our environment so much that we must either change ourselves or, clinging to our memories of the past, try to regenerate the trees that once functioned as our mother. That doesn’t mean, of course, that we should think of protecting the environment to the exclusion of all else, because we do ride in automobiles. We must live with contradictions . . . [A]s with films about trees, I hope I can maintain the perspective that the midges in the ditch near my house are just as important as the prized sweetfish in the clean waters of the Shimanto River.”

(Hayao Miyazaki, Starting Point: 1979–1996, p. 163-64)

WATCH: My Neighbor Totoro (1988)*

By this point, we’ve relived the violent past and taken a glimpse into the war-torn future. What is left of the forest in the present? Well, one could definitely say it’s facing a “quickening end” of sorts. As we continue to permit rapid urbanization, expanding cityscapes, and reckless waste, we trade off forest life for our own proliferation. After Nausicaä learns the truth of the Daikosho, who’s to say what the real virus is: a biological toxin born of natural processes and synthetic manipulation, or unchecked human greed. Both stink, that’s for sure. At least we still have Totoro, right?

Although My Neighbor Totoro was released almost a decade before Princess Mononoke, I find its optimistic spirit a far more pleasant cushion for facing the end times. Part of this motivation circles back to Miyazaki’s own fondness for the children growing up in society. Even when we grumble at a weed poking through the pavement, children can still find beauty in the bramble. The forest trees loom large over Mei and Satsuki’s heads, and their joyous wonder is both amusing and contagious. In a way, the forest and its Totoro give the girls energy and awe out in Japan’s quiet countryside.

*Don’t forget to read the statements from Toshio Suzuki (2012) and Hayao Miyazaki (1986) before OR after watching the film. The only format I presently own these in is the GKIDS Blu-ray release insert, though the director’s statement can also be found in Starting Point: 1979–1996 (p. 255; project plan with more details) and The Art of My Neighbor Totoro (VIZ Media).

READ: Starting Point: 1979–1996 (VIZ Media)

You saw this coming. Flip open your mangled, marked-up, sticky-noted copy of Starting Point and get to readin’! Oh, does only mine look like that? Huh.

- Project Plan for My Neighbor Totoro (p. 255)

- The Type of Film I’d Like to Create (p. 148)

- Things That Live in a Tree (p. 162)

- Totoro Was Not Made as a Nostalgia Piece (p. 350; there are also comments on Kazuo Oga’s artwork)

WATCH: Pom Poko (1994)*

Remember when I said that several Ghibli works approach themes of nature and environmentalism? Pom Poko (1994) is Isao Takahata’s highly beloved crack at the topic, and he does more than snap a few branches. Takahata’s tale of tanuki going “over the hedge” is a landmark in showcasing the modern plight of Japanese forest conservationists. Through depictions across changing seasons in Japan, the film paints over pastoral forest life as urbanity creeps over the canopies one concrete apartment complex at a time. “The forest is magical” is oft cited by Ghibli fans. Between whimsical Totoro, whispering kodama, and wild tanuki, perhaps the forest’s denizens possess equal ability to charm us.

*Don’t forget to read the statements from Toshio Suzuki (2013) and Isao Takahata (1994) before OR after watching the film. The only format I presently own these in is the GKIDS Blu-ray release insert, though I’m sure they can be found online or in print elsewhere.

SUPPLEMENT: Kazuo Oga Art Collection I & II (Tokuma Shoten)

We’ve spent so much time admiring the forest through text and animation, but we’ve labored little in studying the foliage up close. Kazuo Oga is not only a famed background artist but also a brilliant art director. His art directorship notably includes My Neighbor Totoro, Only Yesterday, Pom Poko, Princess Mononoke, and The Tale of Princess Kaguya—all Ghibli works where nature plays a star role. Oga’s background art spreads across too many masterful canvases to name here: Panda! Go, Panda!, Kiki’s Delivery Service, Porco Rosso, Whisper of the Heart, Spirited Away—You get the picture. He’s one of a powerhouse team that has fueled the “Studio Ghibli aesthetic” for decades. And for Princess Mononoke, he traveled far out to the Shirakami-Sanchi mountains to draw inspiration for the Emishi village.

Kazuo Oga’s art collections aren’t available under a U.S. license, but if you can get your hands on at least one of them, you’ll have a friend for life. Let’s spend some time soaking in his legendary forestscapes. If you’re not sure what to “look” for, consider starting with this note, a reflection from Kazuo Oga himself when Miyazaki first critiqued his forest artwork (p. 53):

“I gradually came to understand that I would not be able to achieve the picture that Miyazaki was looking for unless I paid more attention to the relationship between light and subdued colors. Until then, I had drawn trees rather symbolically . . . But I began to feel that I needed to carefully incorporate the many other trees and plants that we don’t usually notice, and the colors of the walls and pillars inside a room . . . The color of the pillars also changes depending on how the light hits them . . .”

Isao Takahata on Oga’s art direction (p. 88):

“Each plant and object is modest, neither standing out nor blending in, but each one exists properly, alive and well. And how charming it is to see them all blend together in a modest way.”

(Quotes are rough translations from Art Collection I via Google Lens.)

Other Ghibli Works to Support Your Forest Expedition

“Even though we [Japanese] have become a modern people, we still feel that there is a place where, if we go deep into the mountains, we can find a forest full of beautiful greenery and pure running water that is like a dreamscape . . . Deep in the forest there is something sacred that exists without a perceptible function. That is the central core, the navel, of the world, and we want to return in time to that pure place.”

(Hayao Miyazaki, Turning Point: 1997–2008, p. 36)

WATCH: Castle in the Sky (1986)

The woes of unchecked technological achievement displacing natural biomes forms a fictional historical backdrop in Laputa. Forests aren’t the center attraction per se, but once you consider the resource tradeoffs an ancient civilization made to create high-flying machines and castles . . . Plus, the overgrowth on Laputa is positively wild, almost as if the trees are reclaiming the castle itself.

WATCH: Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989)

Have you ever felt the urge to escape into the woods, to lose yourself in a place of quiet and sort out all of life’s troubles? Kiki’s retreat to Ursula’s cabin is perhaps one of the most convincing scenes of nature (particularly the forest) offering sanctuary for someone who’s lost their motivation AND rediscovered their creativity—their drive, their spirit—through nature. And I’d fight to keep the film on this “forest guide” if only for an illustrative moment like this.

WATCH: Only Yesterday (1991)

Taeko takes Kiki’s night journey to another level when she decides to revisit her relatives in the countryside. Nature and nostalgia weave together unexpectedly, and past memories bubble forth as Taeko reconnects with the mundane joys of outdoor living. There are many, many flourishing fields and flowers (in no small part thanks to Kazuo Oga), but it’s those majestic mountain forests that give Only Yesterday its sense that love can be expansive, at times arresting, yet always on the horizon.

READ: Shuna’s Journey (1983)

Miyazaki’s only standalone emonogatari (illustrated story) book is a moving work on its own, and it’s an even stronger thematic supplement to Nausicaä and Princess Mononoke especially where nature is visualized. The forest center as a mysterious paradise or “heart” which is home to the collective pulse of all ancient life is a frequently revisited motif in Miyazaki’s works. Given Shuna’s early 1983 publication date, it’s no wonder that the story sowed the creative seeds for many other recurring images, themes, and setting details.

SUPPLEMENT: Hayao Miyazaki (Academy Museum)

Such a dense archival book (both for information and artwork) is worth looking into for forest matters if only because the publication itself highlights Miyazaki’s forests in specific sections. These bits are of special note for us:

- Creating Worlds (p. 121)

- Totoro and the Mother Tree (p. 151)

- The Forest, Kodama, and the Deer God (p. 157)

- Nature and Nostalgia (p. 200)

- Magical Forest (p. 250)

SUPPLEMENT: Studio Ghibli: Architecture in Animation (VIZ Media)

Wait, what does architecture have to do with nature? If you’ve watched any Ghibli film, then you’d know that the two come hand-in-hand. Architectural historian Terunobu Fujimori has put together a way to absorb and analyze Ghibli backgrounds that transcends the traditional art book experience of awe and admiration. His commentaries on the “Point of Contact Between Nature and Artifice” and “Forestry Society” (p. 25) are especially insightful.

Towards Greener Pastures: Ghibli-Adjacent Works

“The major characteristic of Studio Ghibli—not just myself—is the way we depict nature. We don’t subordinate the natural setting to the characters. Our way of thinking is that nature exists and human beings exist within it.”

(Hayao Miyazaki, Turning Point: 1997–2008, p. 90)

READ: The Easy Life in Kamusari (Shion Miura)

This slow-going, slice-of-life novel follows Yuki Hirano, a fresh-out-of-high-school bum who is sent out to the remote mountain village of Kamusari to earn some income through a forestry training program. Although he’s distanced from technology, friends, and popular society itself, Yuki eventually takes on the natural and practical challenges the mountain poses and comes to appreciate the forest for the trees. Shion Miura (The Great Passage, Run with the Wind) pens a teenage boy’s point-of-view with all its growing pains, even referencing a certain Ghibli film to describe the reverential movement of snow-like spores floating above the forest range.

READ: Sweet Bean Paste (Durian Sukegawa)

An international bestseller, Sweet Bean Paste might not have anything to do with forests, but it does discuss the misery, stigma, and effects of a certain disease outbreak and Japan’s historical mistreatment of those affected. I offer it here because, while Miyazaki was working on Princess Mononoke, he would frequently visit the sanatorium grounds (which is next to its museum) and ponder deeply and sincerely about those who suffered. This became part of the inspiration for the infected Prince Ashitaka who henceforth embarks through dense forests to find himself a cure. Sukegawa’s book is also flat-out remarkable for its equally endearing, admirable characters.

READ: Once and Forever: The Tales of Kenji Miyazawa

I haven’t actually read this particular collection of Miyazawa’s classic, fablesque short story writing, but I do know two things: 1) the late philosopher Takeshi Umehara (in an interview with Hayao Miyazaki) cites Kenji Miyazawa as one of “two poets of the forest,” the other being Kumagusu Minakata (Turning Point: 1997–2008, pg. 103); and 2) the NYRB publication of Miyazawa’s collected tales features giant trees on the cover. As a follow-up to this forest journey, this book will be one of my next immediate reads.

WATCH: Mushi-Shi (2005)

There are probably a hundred excellent anime out there that make intellectual, philosophical, and spiritual commentary on the forest like Studio Ghibli works do, but few are more patient than Mushi-Shi. You follow Ginko, an investigator of sorts with the rare ability “to peer into the places where the mushi hide in plain sight,” the mushi being the unexplainable, unseen creatures of nature which have silently attached themselves to our lives. For Ginko, exploring dark forest depths is par for the course, and how he conducts himself in nature is a philosophy in itself.

SUPPLEMENT: Kawase Hasui Artworks – Enlarged Revised Edition (Tokyo Bijutsu)

For this recommendation, any Kawase Hasui art book would do, but I really like this one. A printmaker of the shin-hanga “new prints” movement, Hasui combines the ukiyo-e “floating world” style while incorporating Western atmospheric effects and natural lighting (two attributes which Kazuo Oga strove for in his backgrounds for Ghibli). Since Hasui specialized in landscapes, you will find lots of 20th century (or older) architecture and nature depictions across all seasons and weather types. Studying the shift from traditional two-dimensional ukiyo-e to Hasui’s blended Eastern-Western style and all the way up to Oga’s Western style with Eastern subjects is rewarding on its own. The forest has been a world of inspiration for artists of all forms—and of all generations.

SUPPLEMENT: Art Books by Nizo Yamamoto (Various)

I wanted to squeeze one final recommendation that’s not pictured anywhere in this post. Nizo Yamamoto was an art director and background artist like Kazuo Oga who produced nature art for several Studio Ghibli projects (including the background used in this post’s header graphic). Sadly, he passed away in 2023, but his style is timeless. You can find various art books by the late artist still in print.

Planting a Seed (i.e., What’s Next?)

At just over 5,000 words, this is a project that I’m happy to finally see through to completion. I’ve had reference materials, sticky notes, and midnight movie viewings filling up my creative space for some time, and it’s satisfying to return them each to their respective home on my shelves. One thing you may have noticed is that there’s not much for video or online article sources cited here. That was intentional. With so many materials physically published and Blu-rays released, I wanted to revel in the analog for this project. A quick YouTube search on this topic or adjacent ones will likely spit out what you want, anyhow; this was a purely personal journey, and I simply wanted to share my close-reading methods with you.

That said, with the popularity of the video guide format, I might make a video version of this post for my YouTube channel. It could prove equally fun to hop behind the camera and thumb through the pages for y’all, but no promises. As for other Ghibli posts, Hayao Miyazaki made the forest a real character through his films, yet one could argue he’s even more famous for his films depicting aviation and other magical worlds. Until I find a new topic to obsess over, we’ll leave it at the trees for now.

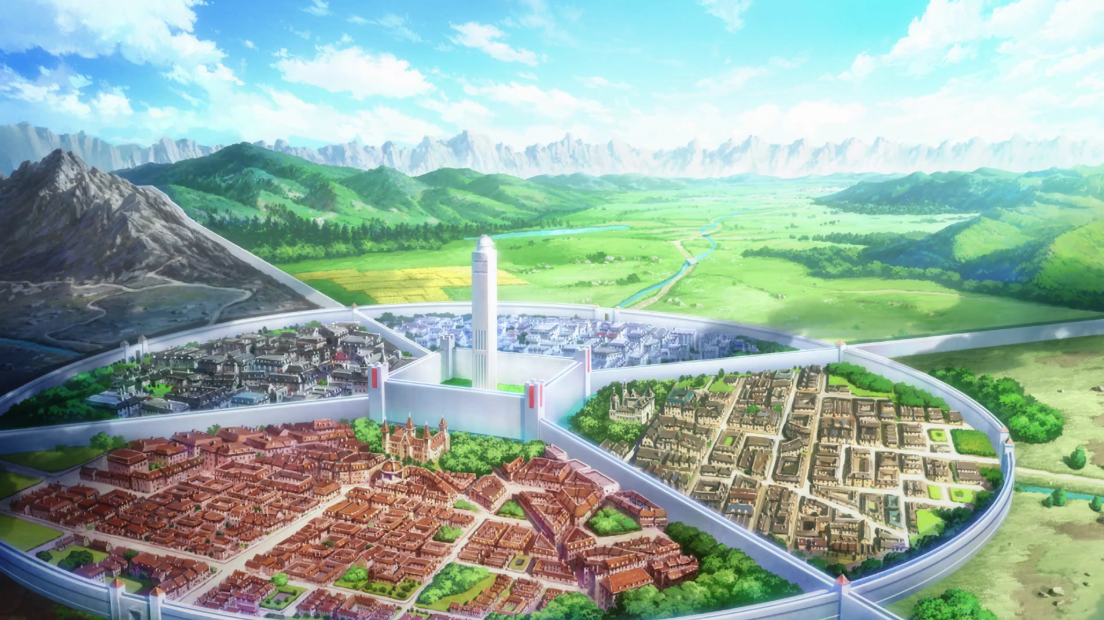

To completely pivot, I’ve got a smaller project on the complete opposite topic currently in the works. Did you guess sci-fi cityscapes in anime? Hah! Think of it as a direct response to this post about life on the forest floor. Throughout fall 2024, I was able to escape into both of these vastly diverse settings. I can’t wait to show you that other half which calls out to me.

Also, I haven’t forgotten about the Makoto Shinkai “revisit” project I started last year! It got shelved for a bit due to other intervening interests, but I do plan to produce something worth reading. Lastly, as February draws nearer, my annual “V-Day Special” anime marathon awaits. More TBA soon.

If you made it to the end, I hope this guide will prove OR has proven helpful to your own understanding of Ghibli forests and nature more broadly. Thank you for your time, and happy reading!

– Takuto